Hi fellow CMIOs, CNIOs, and other applied Clinical Informatics friends,

I'm writing today to share some helpful insights into one of those clinical operations things you don't usually learn much about during clinical education and training : Incidental and other actionable findings.

First, some literature review. Before we dive into this, I'd like to share this excellent 2014 groundbreaking paper from the Journal of the American College of Radiology (JACR) Actionable Findings Workgroup, including Larson MD, Berland MD, Griffith MD, Kahn Jr MD, and Liebscher MD:

Actionable Findings and the Role of IT Support : Report of the ACR Actionable Reporting Workgroup

Also note that the American College of Radiology (ACR) and American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) recently published a joint piece in the March 2023 Journal of the American College of Radiology (JACR), an excellent white paper (click here to open it) about "Best Practices in the Communication and Management of Actionable Incidental Findings in Emergency Department Imaging" (Christopher L. Moore, MD , Andrew Baskin, MD , Anna Marie Chang, MD, MSCE ,

Dickson Cheung, MD, MBA, MPH , Melissa A. Davis, MD, MBA , Baruch S. Fertel, MD, MPA,

Kristen Hans, RN, MS, Stella K. Kang, MD, MSc, David M. Larson, MD,

Ryan K. Lee, MD, MBA, Kristin B. McCabe-Kline, MD, Angela M. Mills, MD,

Gregory N. Nicola, MD, Lauren P. Nicola, MD, JACR Mar 13, 2023). However, since this is an important discussion, I thought I'd share some broader insights into these important workflows from an Applied Clinical Informatics perspective.

It all starts here : In healthcare, there are the routine clinical scenarios, and then there are the unusual, unexpected clinical scenarios. Most of the time, laboratory studies are generally within normal or anticipated ranges, and radiologic studies (X-rays, ultrasounds, CT scans, and MRIs) produce expected or anticipated results.

So when labs or radiology are unanticipated, unusual, or abnormal - they can come in different levels of abnormal :

- Mildly abnormal - Something is unusual that requires special but not-urgent clinical attention (within days)

- Moderately abnormal - Something is unusual that requires urgent clinical attention (within hours)

- Severely abnormal - Something is unusual that requires immediate clinical attention (within minutes)

In all three cases, it's not enough to just deliver the routine results of the lab or radiology to the ordering provider. For patient care and safety reasons, some type of extra communication is warranted.

The three most common reasons for these extra communications all fall under a general category known as 'Actionable Findings' - Note these categories align with the findings from the 2014 JACR Actionable Results Workgroup above :

Now the interesting challenge of these additional communications is the urgency of these additional messages and how they can sometimes conflict with real-world scenarios :

- What if the ordering provider was a resident who has gone home at the end of their shift?

- What if the attending has also gone home at the end of their shift?

- What if both the resident and attending have turned off their phones/pagers or are asleep?

- Who is the covering provider?

- What if the covering provider is busy with urgently caring for another patient?

Given these scenarios, the communication workflow can be a bit difficult to dissect - but I'm happy to share a basic breakdown of what to consider. Hint : It stratifies along the lines of acuity (low, medium, and high), patient location, and ordering provider.

Let's take a closer look at these important scenarios.

1. LOW ACUITY - THE INCIDENTAL FINDING

In this scenario, there is something important that needs to be communicated to the ordering provider but also usually the Primary Care Provider (PCP), usually because there was something unexpected that requires additional follow-up, e.g. an unexpected nodule.

While it's tempting to think that low-acuity (incidental) findings are somehow less important than moderate-acuity (urgent) findings or high-acuity (critical) findings - the truth is that they are every bit as important, only the time needed to address the issue is a little longer.

Stratifying this first low-acuity (incidental) finding scenario by patient location then looks like this :

(Sample workflow for delivering low-acuity, incidental findings)

Since incidental findings require follow-up, it's very important to close the loop with the PCP to ensure the proper follow-up studies have been ordered and the patient/caregiver are aware of the need for follow-up. (New rules from the 21st Century CURES Act and open sharing via the patient portal make this much more transparent for patients today.) To help, some EMR software will record exactly when the PCP has acknowledged receipt of this important message, with important instructions.

2. MODERATE OR HIGH ACUITY - THE URGENT AND CRITICAL FINDINGS

In these scenarios, there is something urgent or critical that needs to be communicated to the ordering or covering provider, usually within an hour or less. Typically, direct provider-to-provider communication is best to help ensure the message has been transmitted and received properly, and an urgent/emergent plan has been put in place.

Communication in these scenarios can sometimes be stymied by schedule/change-of-shift, so an escalation process is especially important for these urgent/critical scenarios :

(Sample workflow for delivering medium-acuity (urgent) and high-acuity(critical) findings)

The exact escalation process you build for your own organization will probably depend on a number of factors, including whether you are a community hospital, teaching hospital, or critical-access hospital. For a great example of a well-developed escalation process, see pages 7-11 of this helpful policy, "Reporting of Critical Results to Providers" from the University of Texas Medical Branch. (Thank you to UTMB for sharing your process for teaching purposes and the betterment of healthcare!)

What's interesting about this escalation process is that it will often depend on a provider schedule; So having access to a centralized, up-to-date provider on-call (coverage) schedule is often helpful in identifying covering providers for various services and clinics, especially when trying to communicate actionable findings after change of shift :

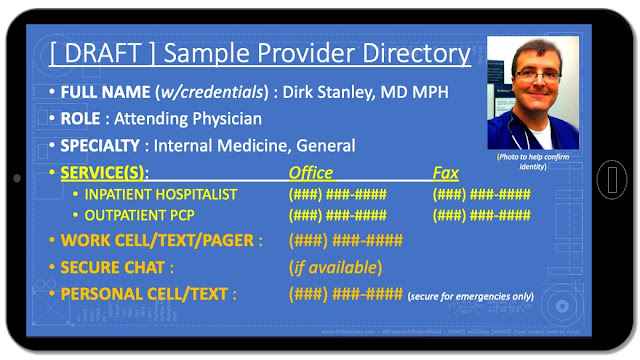

Also, depending on the scenario, having a complete and accurate provider directory is very important, one that properly considers both a providers' clinical specialty/subspecialty (training) and clinical service(s) :

Since most providers will arrive through your Credentialing/Medical Staff office, and most residents/fellows will go through your Graduate Medical Education (GME) office, you will want to collect this information at onboarding, and help maintain it at regular intervals (e.g. recredentialing or yearly assessments.)

And after an urgent/critical provider-to-provider communication has been completed, both providers should document the discussion in their clinical documentation to help ensure the loop has been closed and a plan is in place.

Finally, for providers external to your institution - When designing your forms for ordering labs or radiology, you might consider adding the following language :

(Sample language for external ordering forms, to plan for all actionable finding scenarios)

Having this information somewhere handy (e.g., on the ordering form) will help you prepare for these scenarios when they occur with external providers.

Yes, these are a lot of scenarios to think about - but with the right planning and tools, you can help your staff reach ordering or covering providers to communicate these important messages and close the loop on important patient care.

Remember, this blog is for educational purposes only - Your mileage may vary. Have any experience with these workflows, or experience building them? Or have a perfect escalation process? Feel free to leave comments, feedback, and suggestions below!